We Become Summer by Amy Barone, NYQ Books, 2018, 92 Pages, $15.95

Review by Jennifer Martelli

In her poem, “Soundtrack to My Life,” Amy Barone writes:

I make homes wherever I lay my bag.

“I’ve Got a Line on You,” New York, no longer him.

It’s place that brings me to climax.

Belonging and abandonment, relationships with men and family, music from jazz to pop, are the motifs that act as the weft in Barone’s moving and tactile collection, We Become Summer. Written in five sections that function as the warp of this loom, Barone’s poems are woven into a fabric created from the Italian diaspora, with all the textures of letting go, of leaving. As she states in “Lessons Learned from Moths,”

Celestial nomads that feast on

leather, wool, silk, felt

and thrive on night

taught me to let go of longing—

Barone’s sense of belonging to a clan is underscored by the deep sadness of abandonment of a culture and of movement. Italy and the Italian experience is a constant throughout the speaker’s life. In “Safety,” Barone writes

That same day, I found solace in a quart of beer

on a beach in San Felice Circeo near Rome, abandoned

by Italian cousins who didn’t feel I was family enough.

The long roots of the family (“My origins are rooted in a land of untamed nature”) reach across the Atlantic, to New York and Pennsylvania, “. . . . in the breezeway. / Cousins galore gather ‘round a bakery cake.” In this same home, a place of early rootedness, the speaker begins her exploration of sexuality (and all its inherent disappointments) as well: “At thirteen, I get my first kiss the back yard playhouse. // None of it ever like it played out in the old movies.”

This examination of belonging to—and abandonment by—a culture is echoed in Barone’s poems that examine relationships: the intimate, co-dependent, and the earthy. Barone’s facing poems, “Magazine Street” and “Unfinished,” starkly portray a disconnectedness in the modern, techno world (another theme that mimics the passing from the “old country” to the new). A chance meeting with “a fellow Pennsylvanian and music lover, in NOLA” ends as abruptly as it developed, “But I never saw him again and in those three/Southern minutes, formed a memory.” The severing of relationships is made all the more poignant in “Unfinished,” when the speaker admits, “We stopped speaking, if you call words // sent to a computer screen, on a random basis, talk.”

Barone entwines music throughout the collection; it becomes the designer thread used by Gianni Versace and Paco Rabanne. Music is a sensual, dangerous, exciting stylus, dragging across the surface, forcing song. In “Romance Chelsea Style,” Barone conflates a destructive relationship with music:

He turned me on to songwriters he idolized—

Robyn Hitchcock, Juliana Hatfield, Jane Siberry.

On my birthday he gave a gift that will last forever,

a nameless song that called me the brightest star.

It took me years to wean myself off him,

much longer than it took him to quit the needle.

The drag of the needle—across skin, across a vinyl disc—echoes back to the pull of family and blood. In the poems, “Soundtrack to My Mother’s Life” and “Soundtrack to My Father’s Life,” the speaker laments time’s passage and the immigrant’s passage. Both poems, too, examine abandonment and its DNA-like strands in the speaker’s life. Of her mother, Barone writes: “She deserved better // . . . . as her smile sparkled. It follows me everywhere.” One of the many joys in this collection is how a narration unfolds, like a cloth taken from a drawer. The mother’s song continues in “Soundtrack to My Father’s Life,” when we’re told

He loved Gershwin, big band, opera, marching bands.

. . . . the son of Italian immigrants . . . .

//

The house felt barren after he left.

Abandonment, love, heritage, displacement are continuous melodies throughout a uniquely American story. We Become Summer luxuriates in designer fabrics, iconic music, Italy, the United States. “I’m deporting colorless lingerie and sex,” she writes, “when I sleep, instead of jumping into black puddles, / I’m going to emerge from tangerine dreams. Glowing.” Amy Barone creates a multi-sensual story, in the voice of the Italian-American woman, embracing her hard-earned strength and her blood-rights.

The Short List of Certainties by Lois Roma-Deeley

Franciscan University Press, 2017. 104 pages. $14.00

Review by Jennifer Martelli

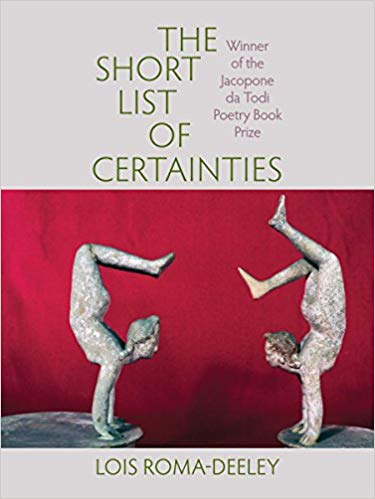

In her poem, “The Dark Night Speaks to the Soul,” Lois Roma-Deeley writes, “Your prayers begin and end unanswered/as echoes in a whirlwind. You’re shattered.” The poems in The Short List of Certainties, Roma-Deeley’s award-winning collection, speak to and from that “shattered” place which requires a straddling of two realities, despair and faith. Quoting St. Augustine of Hippo, Roma-Deeley begins her collection with the daughters of Hope: anger and courage. Even the gorgeous cover photo of an ancient Greek sculpture of two symmetrical acrobats speaks to an agility and a duality that are present throughout the collection which “describes the map/of a woman’s body and its bruises.”

The specter of another world, of a sister-experience, lies like a scrim over the landscapes. In “Mountain Echoes for the Boko Haram Girls,” Rome-Deeley writes

She slides through the gate,

(and this) holding both sides of the jerrycan poised

on the crown of her head in the elegant balance

of blood and bone. This old can (my sister whispers)

will hold a gallon or two of dirty water . . . .

//

hurrying faster now to the spring were (we all know)

behind a strand of trees, men wait and wait—

This sense of two realities occurring, or the possibility of two realities, is ever-present. The pending moment—the balance just before the next move—can ben exhilarating and terrifying, almost acrobatic. In “Angel of a Better Nature,” the speaker describes, “. . . . a wild leap from between to among;//step by forgiving step,/on a dusty highway that stretches between two great cities . . . .”

Roma-Deeley’s poems constantly define and redefine time and events, encompassing not just memory, but regret and re-birth. I thought of a poem by Marie Howe, “For three Days,” where she uses the idea of Schroedenger’s Cat “. . . .that would be dead if you looked//and might live if you didn’t,” to describe these simultaneous possibilities. The heart-breaking poem, “Phoenix, July 2011,” speaks to these parallel words as the poet fears seeing Christina-Taylor Green—the nine-year-old victim of a gun massacre—in those hours before her death:

Don’t let me see how

when the words finally get spoken

Christina-Taylor Green will nod yes yes yes

//

And before they go into town,

keep me from fully understanding

how they will feel

when, in this precise and unending moment

each will come to believe

the human heart is plain but it is not simple.

Seeing and re-visioning are the power and the hope in this collection. Roma-Deeley infuses the despair with a boldness. In “Materializing in Another Life,” she writes,

We won’t be poor.

I’ll be smart enough. Sister, you’ll be thin enough.

My heart won’t grind against itself, and

the landscape won’t erupt every time

we tremble with desire.

Images of rising and looking up recall prayer, “like a tornado sucking up trees, trucks, telephone poles, pigs/whole towns—you name it—/to be taken with certainty, not pity . . . .” The sun in the desert rich with “ocotillo/and cholla, jackrabbits and screech owls” stares down at the poet “like the unblinking eyes of God.”

For all the brokenness in life, Roma-Deeley exalts the every day, “Salt on the tongue. The way snakes moves through the open reaches of Iron Mountain.” The poems in this collection speak to our fear, and from our fear, the duality of hope and courage. As Lois Roma-Deeley writes, “In another time, I might have been/a goddess . . . . but now, I cower in the moonlight.” The power is found in the voice, “the purifying mouths.” The Short List of Certainties is a necessary book for our troubled and troubling times; it is a book that speaks to us with honesty and sorely-needed humanit

Via Incanto, Poems from the Darkroom, by Marisa Frasca, Bordighera Press, 2014

Review by Jennifer Martelli

In her poem, “Photo of Hunchback Woman on the Battlefield, “ Marisa Frasca writes:

Crossing Piazza Kalsa where Cala Bay once formed Palermo’s port,

the hunchback woman with cane hears the old joke: First thing

when you get home from work in the evening, give your wife a good

beating, you may not know why you’re hitting her, but she certainly does!

Violence against women, women transforming and assimilating, and the lush landscape of Sicily are captured by the lethal gaze of the “photographer God’s daughter.” In Via Incanto, Poems from the Darkroom, Marisa Frasca’s poems develop like photographs, displaying images with visceral heft. Listen and feel the description in “Sicilian Blood Oranges,” as the poet experiences color, emotion, and physical pain:

Every time I bled

I saw oranges

ripe Sicilian blood oranges

hit the ground

I kicked their teeth

until the blood

stopped flowing.

The father’s photographic genius—“fixing the deformed”—was passed down to the speaker who learned how to “erase/hand calluses, facial warts, aging lines—.” Photography is a means of capturing the tactile and emotional layers of the immigrant, the blended woman.

In her heart-breaking poem (with an Italian translation on the facing page), “When It Rained Red and Orange Petals,” Frasca writes

This is the last photograph of us in father’s studio:

Mother, Father, Aldo, me in angora sweater with Lurex thread.

Before the camera flashed I grabbed their hands,

hers close to my chest, his nearer my face. I would need that moment

before New York City, when I longed to climb skyscrapers . . . .

Part of me remained behind on that island of olives and plums running. . . .

. . . . where we were still one, and I belonged somewhere

whole.

Just as the speaker’s assimilation into America is captured in the photo, so is her transformation into a sexual, sensual woman. In “The Viewer’s Eyes,” Frasca describes a portrait in her father’s studio:

A lotus brooch in the middle of an artichoke hairdo, full lips

slightly parted; languid almost eyes said I’m a woman . . . .

I found my little

button as I stared at Vanda one afternoon while the family napped.

I knew not where Vanda ended and I began . . . .

As I read Via Incanto, I thought of the trinicria, Sicily’s symbol, formed by three bare legs bent, running, representing the three points of the island. Some say these are women’s legs, so beautiful, they take away one’s breath. Frasca’s feminine voice becomes this island nation, with its colors and fertility, its war and violence. The hub of the trinicria is the head of Medusa, the snake-haired Gorgon, a victim of rape, transformed into a monster. But, she is a monster with great power, strengthened by this violent transformation. The speaker, too, becomes Sicily, or is transformed by Sicily. In “Amore Muto,” Frasca writes

I’m Etna, pizza, mozzarella, mother’s heart.

Suck pain like your mother sucked marrow

from osso bucco . . . . stop

resisting the spent flame—tarantella,

mandolins, the pu ti pu

and Cavalleria Rusticana’s blood-feud.

Frasca’s use of Italian—side-by-side translations of the poems or a peppering of phrases within the poems—changes the depth and flavor. The poems sound different, more musical, exotic. This also illustrates the “hyphenated-woman,” the Italian-American. “She practices hard to lose her accent,” Frasca writes in “Yearning for the Lips of Others.” In “Transforming the I,” Frasca responds to both the sexuality and the shame of the Italian-American, or the Italian in America.

Guinea shame had passed. I was chic; I thickened

my accent, got drunk on men who followed my ass.

//

before retracing my steps to a crumbling Brooklyn tenement

lowering my head, hand over my mouth I entered

the old dark and narrow hallway of the immigrant.

Images of female sexuality and the ensuing violence are as integral to Via Incanto as Medusa’s rape was to her transformation. Frasca stares down the violence, petrifying it, turning it still as stone. In the horrific poem, “More Sicilian Sickness,” a snapshot-size poem depicting a forced clitoridectomy, the speaker

. . . . became gorgon Medusa

whose head of snakes aimed to turn the grand-bitch

to stone. She became an elder holding

my legs open for clitoral mutiliation, tossing

holy hood and labia to Dog God . . . .

The poems in Via Incanto are created in a darkroom, but develop within the gut, in the womb, and transform. Yes, “our culture wages an imbecile’s war on women,” but Frasca has captured that war within the boundaries of photographs rich with the colors, tastes, and sounds of Sicily on the tongue. Marisa Frasca, in her poem, “Aurora,” invokes this different goddess of sunrise when she asks:

And otherness comes down hard:

where have you been hiding

Dark feminine of the moon?

who is this I? Who is this you?

The poems of Via Incanto are radiant in their femininity, gathering strength by encompassing a deep, rich, plum-dark story as their own.

.

Paterson Light and Shadow, Maria Mazziotti Gillan and Mark Hillringhouse.

Reviewed by Jennifer Martelli

Black and white photography is a choreography of nuanced tone: the eye is drawn to the reflection of light, how it dances against the dark. Mark Hillringhouse’s photo, “Winter Falls,” depicts a cold, partially frozen river, barely mirroring the sky. The bare tree branches could be shadows. The falls, white-braided with deep gray, seem frozen in motion. The city–Paterson, New Jersey–is blurred in the background. It must be overcast or near nighttime: two white spots glow far away–headlights. I could be watching a movie frame at “Big Joey’s house . . . . on his father’s 16 mm projector” in Maria Mazziotti Gillan’s accompanying poem, “In the City of Dreams: Paterson, NJ.” Paterson Light and Shadow, a collaborative homage to a city rendered in Mazziotti Gillan’s honest, unflinching poems and Hillringhouse’s stark yet gentle black and white photography, never shies away from the shadows of an aging, working-class city populated by generations of immigrants. The artists contrast the shadowy shame of an old-country heritage with light that exalts the ordinary.

In Mazziotti Gillan’s poem, “17th Street: Paterson, New Jersey,” the speaker’s parents–who embody the Italian immigrant experience and all of its nobility and anachronism–become part of the photographic landscape. Mazziotti Gillan writes:

. . . . the open look on my father’s face, sparks flying from him in pleasure, my mother’s hand, delicate, the charm of those moments where I rested in the luminous circle of love.

Facing this prose poem is Hillringhouse’s “Passaic River Winter Tree Branches.” We are drawn to the center of the photograph–the center of the river–by a misty light. This is the deepest point of the river, where the light falls. Delicate and bare branches reach across the river, like arms.

Hillringhouse’s capturing of reflecting light–and of light reflecting–is probably best seen in his photographs “Bendix Diner,” which depicts the inside of a vintage diner: stainless steel appliances, spotless counter top, glass bricks. The sunlight shines on surfaces, walls, those strips of metal around the faux-leather counter stools. Through the frosted windows we can see bare tree branches. Mazziotti Gillan’s poem, “Jersey Diners,” speaks of this light, “ . . . . Looking back, I see our young faces/lit by the harsh diner lights.” This is a poem mourning the inevitable passage of time, employing similar light and shadow techniques:

the diners glowing only in memory, in all their tacky

glory, and we, our faces still untouched by grief and loss,

caught and framed in the diner’s windows.

The speaker’s parents embody the conflict of the first or second generation of immigrants: a love for this “protected/and safe” community and a deep shame. In her heart-breaking poem, “Daddy, We Called You,” Mazziotti Gillan addresses the contrast of both cultures. At home her father was “Papa//but outside again, you became Daddy.” Mazziotti Gillan’s poem, like a Hillringhouse photograph, uses light and shadow to convey an emotional depth, “Papa, how you glowed in company light,/when the other immigrants/came to you for health. . . .” The father remains illuminated, even as the daughter, embarrassed, denies him:

You were waiting for the bus, the streetlight illuminating your face. I pretended I did not see you, let my boyfriend pull away, leaving you . . . .I was ashamed to have my boyfriend see you, find out about your second shift work, your broken English.

The glowing circle the father creates in the home enables the poet the opportunity to find her voice. My favorite photograph is “Spruce Street Factory Warehouse with Figure.” Like an Escher drawing it demands study with its geometry and depth. A seemingly simple, flat face of an old building with dark paned windows, the drama plays out with the fire-escape zig-zagging up and down the facade. Or, is it the shadow of the fire escape? Which way do the stairs go? This factory, like the factories “Papa” and the millions of immigrants worked their second or third job, allowed the next generation a way out, an escape. The father’s stoic toil allowed the poet to bloom, “to go to college. . . .to absorb the feel of the city. . . .to carry the voice of the people, my people, in my head, to hear their stories, and save them to tell.”

Both artists display Paterson’s rich and reflective life, its voice. The frozen river in Hillringhouse’s opening photograph is thawed in the closing photo, “Passaic River from Lincoln Avenue Bridge.” The poet’s voice is like the water that surrounds Paterson Light and Shadow. “I hear these people who are so much a part of my life, their voices caught like music in my mind,” Mazziotti Gillan writes. The poems and photographs are constantly moving from light to dark, from stasis to movement, ice to water: “I had to cry a long time before I could learn to sing their songs, as my own.”

***

The Things a Body Might Become by Emari DiGiorgio

Reviewed by Jennifer Martelli

In her poem, “Too Small to Be an Amazonian,” Emari DiGiorgio writes

Oh, to be the busty, gun-slung

broad with enough mascara to match her ammo cache. Instead, a brow

creased with loss. A root system in the palm of my hand. My eyes: the

only rosary I carry.

Images of violence and trauma—suicide bombings, mass shooting—transform not only the geography of the world, but the landscape of the soul and the female body in DiGiorgio’s debut poetry collection, The Things a Body Might Become. The reader is confronted with global horror that demands, in return, violence, bravery, and finally, a sense of unity and home. We, along with the speaker, are changed by these experiences.

Women transform themselves as they vie for control and power in an unsafe world. The women wear their protection, become the weapon. In “Electric Lingerie” the speaker claims

Because studies show a rapist will grab

the bosom first. Here is a bra with enough juice

to jumpstart a Greyhound bus, a woman

who can stride the streets of Chennai with confidence.

This attempt at control is mirrored by the woman in “Close to the Edge” who “straps the bomb-purse beneath her Salwar/might believe her life a sacrifice, this death honorable.” Much like Jamie Sommers in the classic television series “The Bionic Woman,” the women in The Things a Body Might Become are hybrids: part female, part weapon or stone or hardened shell. All have been made stronger after trauma, which is the transformative agent. The voice of the mother of a Sandy Hook victim in “Firing Point” who wishes “to hold a gun in my hand . . . . until I empty the chamber between the eyes,” is echoed in the poem “Bullets,” by the woman who digests weapons and laments, “there are so many ways to eat ammunition./Hot bullets in honey.”

The speaker, too, is a hybrid: part modern-day American, part old-country Italian, “a woman in a man’s word, a mother // in a dangerous world.” The women in the speaker’s own family are presented as goddesses. Listen to the beauty of genetics in “Heirloom,” when the speaker describes her flinty lineage:

but the stone has slipped

beneath my skin. Here, above

the heart. The women in my family

must’ve inherited some magnet

in our mother’s wombs, the stones

shaping pyramids in our breasts.

An ancient aegis protects the speaker, her own heart “carved in relief, a cameo of Athena– / onyx chest-plate, narrowed eyes.” This protection will be passed down to the next generation, the speaker’s daughter:

She’ll be

the most painful kind of fearless, an ant who carries

a hundred times her weight in heft and grief.

She’ll want to be a princess even if she denies it

because she’s royalty, as all children are . . . .

As I was reading The Things a Body Might Become, I thought of Jorie Graham’s poem, “Hybrid of Plants and of Ghosts,” where she writes, “I understand that it is grafting, / this partnership of lost wills, common flowers.” DiGiorgio creates a magnificent “other” from the wounded, the powerless, and the women searching for healing and completeness.

By arranging the poems so they speak first to global tragedies, and then inexorably threading repeated images throughout the book, DiGiorgio distills the focus down into the home and creates a closed form: a circle. The roundness of oil heating in a pan in the opening poem, “Close to the Edge,” where the speaker ponders “Is it selfless or selfish to kamikaze, to hijack a 755,” re-appears in the last section of the book where the speaker prepares eggplant to “fry with olive oil.” The cameo is resurrected in the poem “When Emari DiGiori Vaccuums,” when the speaker remembers her grandmother’s cooking, “When Angela Ferrucci died,/the family parceled out the last sauce stacked under the basement // steps. These were her cameo brooches.” The egg the speaker rolls “close/to the edge” and who will “cradle it between my feet,” finds safety in one of the last poems, “Understanding Dear Alice’s Dilemma,” when the speaker states, “A bird in me has hatched.”

The Things a Body Might Become is a powerful collection: unrelenting in its imagery, lethal in its language. Emari DiGiorgio asks us, “When does a girl make a fist?” The voice in this collection is a fusion of experience, heart-breaking attempts at faith and power in a world that can break us all. DiGiorgio has written an important, timely book that exults the wounded. “Some are born/with God’s thumbnail in their wrist.” We feel that pulse pushing against the scarred, healed skin.